Gallery Sofie Van de Velde, Antwerp

22 April – 31 May 2015

Kirstin Arndt

Franka Hörnschemeyer

Olaf Holzapfel

Charlotte Posenenske

Michael Reiter

Martina Wolf

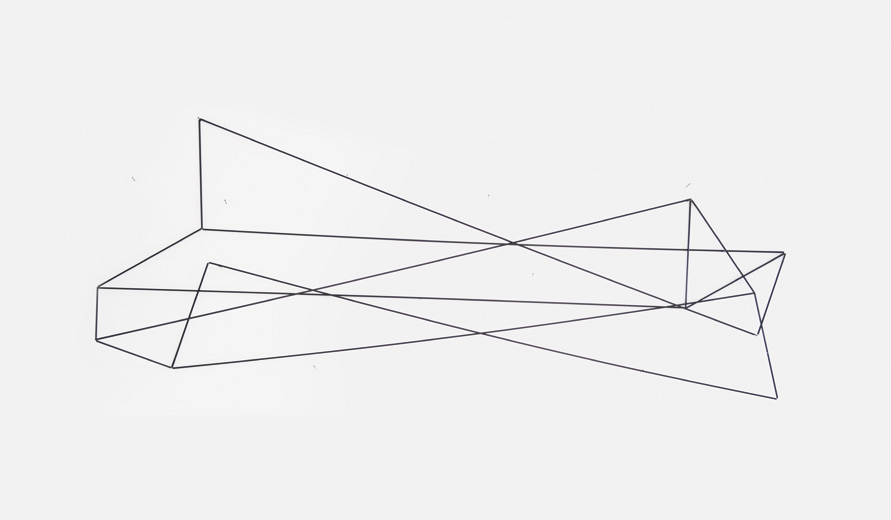

Ausstellungsansicht. Franka Hörnschemeyer. Galerie Sofie Van de Velde. Antwerpen. 2015

That’s all. In Europe, the roots of minimalism, which in the United States became a specific art movement that was then labelled Minimal Art, date back to Classical Antiquity. It is a basic attitude to life that is revealed in art, architecture, design, and literature – less in the form of an explicit movement than a subliminal trend that occasionally surfaces. First evidence of it was in Laconia, the Ancient Greek region of the Spartans, who, in contrast to the flowery manner of speaking of their oriental neighbors, prided themselves on saying anything important in just a few words. Hence the expression “laconic”. The Roman upper class, which adopted Greek culture, placed great store by terse phrases such as Caesar’s “Veni, vidi, vici” (I came, I saw, I conquered) and Vespasian’s “Pecunia non olet” (money does not stink). As a voluntary restriction, Minimalism at all times also represents a conscious attempt to stand out from a decorative style, which favors grandeur, abundance, and detail. The minimalist and the decorative forms of culture, two trends that are frequently mutually dependent, are particularly evident in 17th century Dutch still lifes. In Catholic Antwerp, Frans Snyders was the defining Old Master who portrayed arrangements of fruit, vegetables, game, poultry and seafood in a style showcasing the surfeit of nature. The abundance corresponded with the taste of his aristocratic and bourgeois clients, who as landowners and then as merchants with global operations wished to demonstrate their wealth as social power. In Protestant Haarlem, on the other hand, the minimalist trend culminates in the still lifes painted with such great sensitivity by Pieter Claesz: the most frugal images depict nothing more than a herring, a glass of beer, and a piece of bread – the basic foodstuffs of the populace. These small paintings express the modesty of Protestantism, intended to be pleasing to God. Waste characterized the nobility, thrift the early bourgeoisie. In asceticism, the minimalist restriction to just a little becomes renouncement: when Diogenes, the Cynic philosopher, saw a boy scooping water with his hands, he threw away his beaker, his last possession. For him it was about emancipation from the burden of belongings. There is also evidence of the minimalist trend in the unpretentious design of Biedermeier furniture and then in the radical architecture of Modernism, which according to Adolf Loos’ famous motto of “ornament and crime” freed buildings from all decoration: eclectic facades of the Wilheminian era were erased. Minimalism overwhelms observers not as a result of all manner of details, but rather by giving them the distance they need to try and understand what they are actually looking at. The pictures and objects themselves are straightforward, the complexity only reveals itself in the mind.

The few works by Kirstin Arndt, Franka Hörnschemeyer, Olaf Holzapfel, Charlotte Posenenske, Michael Reiter and Martina Wolf form part of this tradition. The reduction conceals the self-confident claim “that’s enough”. Though conceptually different, all the works exhibited are minimalist in the sense described. Burkhard Brunn

Dat is alles. Het Minimalisme, dat in de Verenigde Staten vorm kreeg als de kunststroming Minimal Art, vindt haar wortels in de antieke oudheid van Europa. Het is een grondhouding tegenover het leven die zich in de in de beeldende kunst, architectuur, design en literatuur manifesteert - niet zozeer als een expliciete beweging maar eerder als een grondstroom, een tendens die occasioneel opflakkert. De eerste uiting hiervan was te vinden in Laconia, de Oudgriekse regio van de Spartanen, die zichzelf roemden om hun gave het belangrijke in weinig woorden te kunnen vangen - in contrast tot de bloemrijke spreekwijzen van hun Oriëntaalse buren. Dit verklaart dan ook de herkomst van de uitdrukking ‚laconiek‘. Grote waarde werd gehecht aan bondige zinnen, zoals Ceasar‘s „Veni, vidi, vici“ (Ik kwam, ik zag, ik overwon) en Vespasian‘s „Pecunia non olet“ (Geld stinkt niet). Als een zelfopgelegde restrictie is Minimalisme een bewuste poging om zich te onderscheiden van de decoratieve stijl die grandeur, overvloed en detail representeert. Minimalisme en decoratie zijn cultuurvormen die elkaar nodig hebben om zich tegen elkaar af te kunnen zetten. Beide trends komen vooral tot uiting in zeventiende-eeuwse Nederlandse stillevens. In het Katholieke Antwerpen was Frans Snyders de bepalende Oude Meester, die de weelderigheid van de natuur ving in het portretteren van arrangementen van fruit, groente, wild, gevogelte en zeevruchten. Deze overdadigheid kwam overeen met de smaak van zijn aristocratische en bourgeois cliënteel: de landeigenaren en globaal opererende kooplui demonstreerden hun rijkdom als een sociale macht. Anderzijds bereikte in het Protestante Haarlem de minimalistische trend haar hoogtepunt in de met grote sensitiviteit geschilderde stillevens van Pieter Claesz. De soberste werken laten niet meer zien dan een haring, een glas bier en een stuk brood: het basisvoedsel van het gewone volk. Deze kleine werken tonen de bescheidenheid van het Protestantisme, dat er op gericht was om vooral God te plezieren. Terwijl verspilling de nobiliteit karakteriseerde, kenmerkte spaarzaamheid de vroege burgerlijkheid. In ascese wordt de minimalistische beperking tot ‚weinig‘ zelfs een verloochening: wanneer de Cynische filosoof Diogenes een jongen water met zijn handen ziet scheppen werpt hij ook zijn laatste bezit - een beker - weg als daad van zijn bevrijding van de last van het bezit. Er is ook een minimalistische trend in de onpretentieuze ontwerpen van Biedermeier‘s meubels, en in de radicale architectuur van het Modernisme waarin volgens Adolf Loos‘ beroemde motto ‚ornament en misdaad‘ gebouwen bevrijd zouden worden van alle decoratie: de eclectische en rijkversierde gevels van de Gründerzeit werden uitgewist. Minimalisme overweldigt de toeschouwer niet door een veelheid in detaillering maar laat eerder een afstand toe die hem helpt te begrijpen wat hij ziet. De beelden en objecten zelf zijn eenvoudig in hun verschijning: de complexiteit openbaart zich in de geest.

Binnen deze lange traditie horen de werken van Kirstin Arndt, Franka Hörnschemeyer, Olaf Holzapfel, Charlotte Posenenske, Michael Reiter en Martina Wolf. Achter de reductie staat de zelfbewuste uitspraak: „Het is genoeg“. Hoewel de tentoongestelde werken conceptueel verschillen, zijn ze allen in die zin minimalistisch. Burkhard Brunn

Olaf Holzapfel

Brücke mit Häusern

Michael Reiter

Jolly Trellis

Charlotte Posenenske

Square Tubes Series D

Martina Wolf

ICE