Gallery Mehdi Chouakri. Berlin

12. January – 23. February 2018

Kirstin Arndt

Cécile Dupaquier

Charlotte Posenenske

Franziska Reinbothe

Michael Reiter

Gerwald Rockenschaub

Willy de Sauter

Rob Scholte

Martina Wolf

Exhibition View. Mehdi Chouakri, Fasanenplatz, Berlin. 2018 (Foto: Michael Reiter)

Exhibition View. Mehdi Chouakri, Fasanenplatz, Berlin. 2018 (Foto: Michael Reiter)

Backstage: The Rear Side. The “Barberini Faun” in Munich’s Glyptothek has a coarse rear side, as originally it was joined to a garden wall. The faun is asleep and is presumably drunk. His legs are splayed apart and his genitals are displayed without shame. In the 19th century the museum attendant would guide ladies past the shocking front side to the rear: There, barely visible, a small tail protrudes. Thank heavens, it is an animal! The front of an artwork can conjure up illusions (a well-endowed young man), but the hidden rear side reveals the truth (an animal). Similarly, the “Vanitas” figure on Strasbourg Cathedral reminds us of the inevitable truth, for while the front shows a beautiful woman, the rear is a nest of worms – a dramatic symbol of transience. In the context of theater, we use the word ‘backstage’ to describe what happens behind the stage. It is here – hidden from public view – that we find the technical equipment that enables the play to take place on the stage. These are the non-aesthetic conditions for work. On the stage we have the entrancing diva, backstage the untidy dressing table, etc. The Centre Pompidou has no façade, no front side. You look directly into the insides of Renzo Piano’s building: pipes, cables, bracing. What you see is not the mask that traditionally fronts a building, but rather what it normally hides, namely the structure. In front – the brilliant product, behind – the conditions and traces of work: with pictures the stretchers, the frame, the mounting, stickers, information on the exhibition venues – the rear, which Antwerp-born Cornelius Gijsbrechts painted as a still life as early as 1670.

For our exhibition: Rob Scholte uses embroidered pictures he found at flea markets, fashioned by Dutch housewives using patterns (Vermeer, Rembrandt and others). He turns them over, signs the back and exhibits them. What people now see are the threads hanging out, which close up look like undefined patches of color, but from a certain distance reveal the picture – as in an Impressionist painting. Charlotte Posenenske’s Diagonal Folding reveals the hanging used on the rear. Unlike traditional sculpture, the stereometric hollow bodies provide a view of the interior. Cécile Dupaquier folds part of the rear forwards. Similarly, Michael Reiter’s objects reveal both the front and rear sides at the same time, as do the large loops in Kirstin Arndt’s net. It recalls the Mobius strip, where the front becomes the rear and vice versa. Franziska Reinbothe addresses the conditions of the rear side: frame, canvas, mounting. In this manner the rear side becomes part of the front side. Willy de Sauter’s work stresses the rough sides of the picture normally hidden under the frame. Gerwald Rockenschaub’s work shows the large screw with which it is attached to the wall, unashamedly in the middle of the front. In Martina Wolf’s video work the cardboard lid of a fast-food container suspended on a thread from a window handle turns in such a manner that sometimes its shimmering aluminum coating is visible – the inside, on which the space behind the camera appears vaguely, and sometimes its dull front side. All the exhibited works follow in the tradition of enlightenment, in as far as they reveal what is otherwise hidden – the opposite of Mannerist enigma. Burkhard Brunn

Cornelius Norbertus Gijsbrechts

(ca 1610 – after 1675)

1670. Trompe l'oeil

The Reverse of a Framed Painting

66,4 x 87,0 cm

SMK Statens Musem for Kunst

National Gallery of Denmark

The perfect illusion. The only painting in the world that has two reverse sides was painted by Cornelius Norbertus Gijsbrechts in 1670. Born in Antwerp, but whose year of birth and death are unknown, the artist was a brilliant painter of still lifes, who mastered the art of painting illusions perfectly. The 17th-century trompe-l’oeil was produced for fun – we can imagine how Gijsbrechts’ reverse-side painting leaned against a wall in a gallery and how, puzzled, a curious art enthusiast could not help but turn it around the other way, only to be confronted once again with a reverse side. As early as the Renaissance, Florentine patricians took much enjoyment in creating playful deception, and here and there they were continued in their palazzi as illusionist architecture. Strictly speaking, perspective painting as a whole is an illusion, as it feigns three-dimensionality on a flat canvas, an illusion that only modern painting decisively shattered. Trompe-l’oeil painting becomes an exaggeration of general illusion when its naturalism moves the observer not only to observe, but also to take action – namely to rush up, say, to catch, with great presence of mind, a (perfectly painted) glass that appears to fall out of the picture frame. Indeed, Gijsbrechts became so famous for his “Steckbretter” generating such optical illusions that he was appointed to the Danish court. (Steckbretter are shelves affixed at eye-level in the entrances of Dutch townhouses used for quickly depositing odds and ends like letters, spectacles or keys, etc., objects that, in order to achieve the startling effect, were often painted beyond the painting’s edges.)

It is without doubt an affront to hold up to the observer the completely empty reverse of a picture rather than making his or her mouth water with a wealth of tasty delicacies, as was common with most still lifes. Yet going beyond the fun factor, this impudence has a certain depth in that it confronts the observer with emptiness, i.e. nothingness.

Here however, we need to consider that according to Western thinking, nothingness is equivalent to death. Seen thus, Gijsbrechts’ painting is an especially sophisticated version of the memento mori motif frequently featured in still lifes (usually a candle whose flame is dying, a wine glass that has fallen over, a rotting piece of fruit or – all too obvious – a skull), which reminds the observer when enjoying these earthly delicacies to think of the inevitable

end. Gijsbrechts’ painting follows in this tradition. Burkhard Brunn

Charlotte Posenenske

Square Tubes Series D

Tate Modern. London. 2013

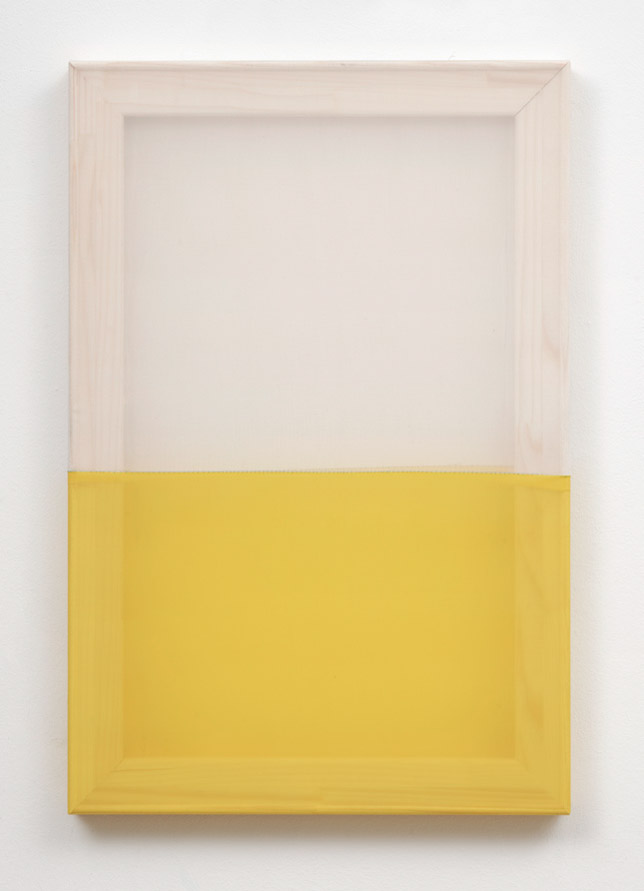

Franziska Reinbothe

ohne Titel

2018

Acryl auf Polyester, Leinwand

40 x 30 x 6 cm

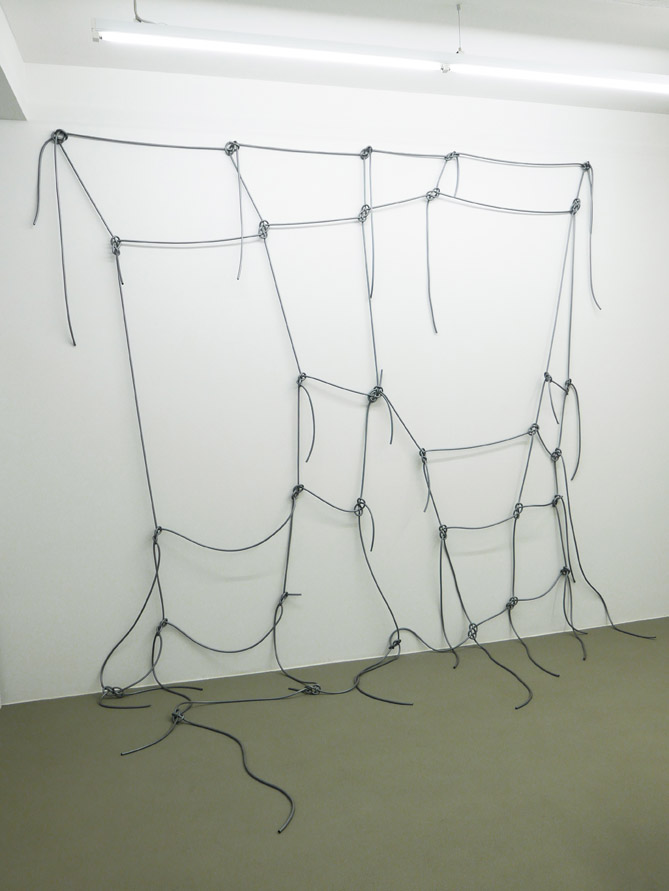

KirstinArndt

untitled

2018

PVC rope (10 mm), screw hook

275 x 275 cm

(Foto: Michael Reiter)

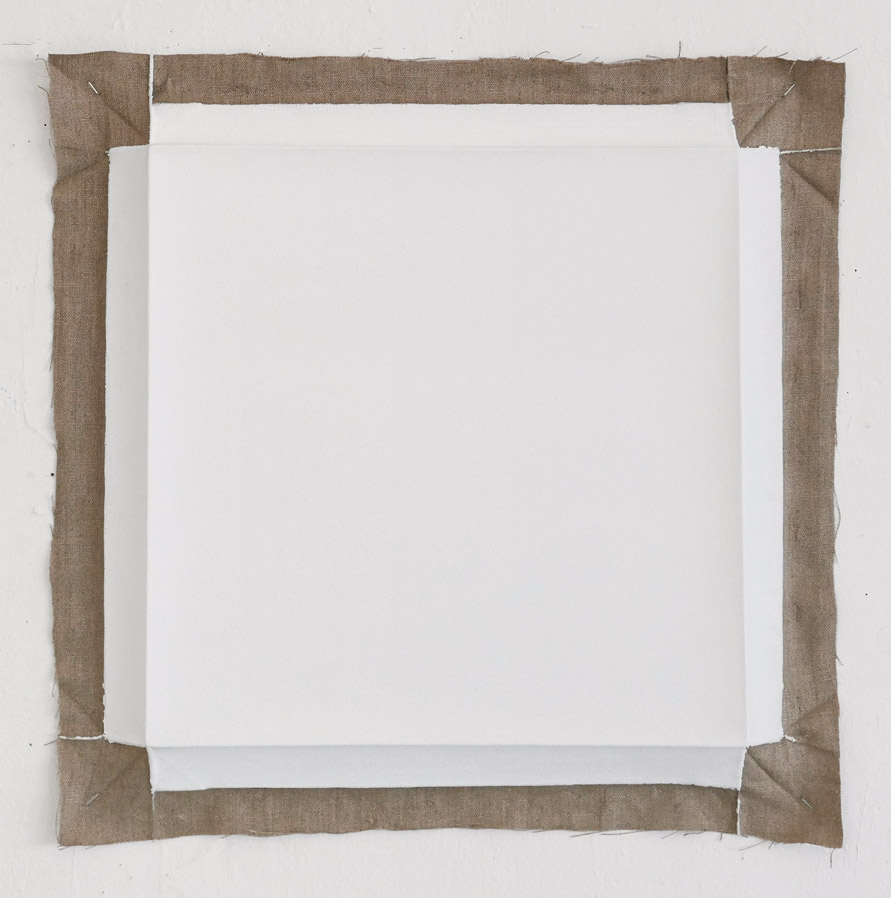

Willy de Sauter

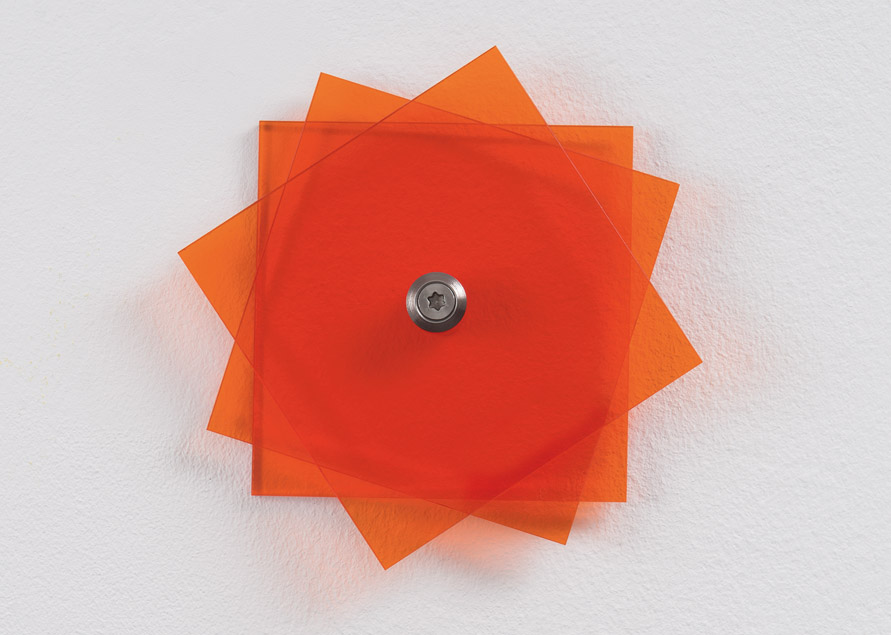

Gerwald Rockenschaub

Cécile Dupaquier

Tableau n°1

2017

Plywood 2mm, silicat paint

86 x 59,5 x 12 cm

Michael Reiter

ridoftheframe

2017

Colour, canvas

50 x 50 cm

Martina Wolf

Rear Side #17

Frankfurt am Main. 2017

HD Videos / Photographs / Montage

Quicktime Movie H.264

1920 x 1080 px / 25p

Mute. 13 min. Loop

Further Exhibition Views (Photos: Michael Reiter)